Harvard economics professor Roland Fryer, Jr., in what he calls “the most surprising result of my career,” found in a new study that during police-civilian interactions officers were not more likely to shoot African Americans than whites.

After the New York Times reported the study, conservative outlets were quick to declare “Harvard Study Debunks Shooting Myth” (Commentary Magazine), “Does Race Play a Role When Police Kill Civilians? The Crime Data Say No, Not Likely” (National Review), and even “The New York Times and the Left Have Blood on Their Hands” (Real Clear Politics) — because apparently both have been pushing lies that ended up killing officers in Dallas (the writer didn’t explain why the Times would break now from its liberal propaganda and publish information that countered the narrative of its untruthful agenda, but no matter).

The results of Fryer’s study are encouraging, but should be taken with a grain of salt, as anyone who actually read the New York Times piece or the study itself might surmise.

First, it’s wise to keep in mind what police departments (and how many) were examined. The study looked at about 1,300 shootings in 10 police departments in three states from 2000-2015. Cities included Houston, Austin, Orlando, Los Angeles, and Jacksonville. The Times noted that Fryer’s

results may not be true in every city. The cities Mr. Fryer used to examine officer-involved shootings make up only about 4 percent of the population of the United States, and serve more black citizens than average.

Though 10 police departments of 12,000 in the U.S. may or may not be an adequate sample size, perhaps more important is that the areas examined had higher black populations, which could have a positive effect on police-minority relations.

via The New York Times

After all, Intergroup Contact Theory, the idea that increased contact between majority and minority groups reduces prejudice, is well established, and studies specifically relating to African Americans and the police align neatly: a 2006 study showed that “officers with positive contact with Black people in their personal lives were particularly able to eliminate [racial] biases with training.” Police departments around the country are trying to increase contact between the officers and the people they serve. Areas with more African Americans may have more African American police officers, too — a benefit for both white officers and relations with the black community.

In other words, it could very well be that American cities and towns with fewer black citizens — less interaction — may see more bias in police shootings.

And, as Dara Lind wrote,

Different cities have different approaches to police-community relations; different tensions; different standards for use of force… In fact, the cities Fryer and his team worked with are all members of a White House initiative on policing data launched in 2015 — and the kind of department that thinks data collection and transparency are important is likely to have different priorities in other regards than one that isn’t.

The 10 police departments involved in this study may be more pro-active in preventing police abuse than others.

Secondly, the 10 departments were examined to see who the police shot at and what the victims were doing (for example, “Black and white civilians involved in police shootings were equally likely to have been carrying a weapon”), finding they shot blacks and whites at equal rates, but this didn’t examine frequency of encounters — and higher frequency can mean a higher death toll. Fryer and colleagues, as the Times puts it,

focused on what happens when police encounters occur, not how often they happen. (There’s a disproportionate number of tense interactions among blacks and the police when shootings could occur, and thus a disproportionate outcome for blacks.)

In other words, Fryer did not look into the frequency of incidents and how that might affect the total killed. He looked at what happened when there was an incident. So even if, and we can hope this is true, cops shoot blacks and whites at equal rates, wouldn’t increased incidents lead to higher death tolls for blacks — not just increased incidents resulting from blacks disproportionately living in poor neighborhoods, which tend to have higher crime, but also through police harassment and racial profiling, where blacks are much more likely to be pulled over or searched than whites exhibiting the same behaviors (which Fryer did find to be a severe problem)?

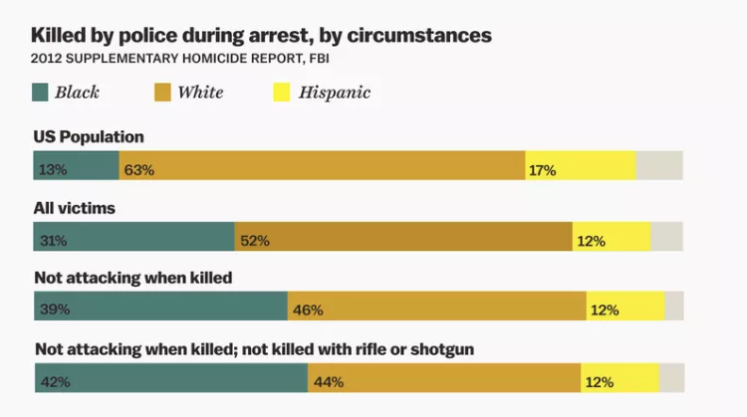

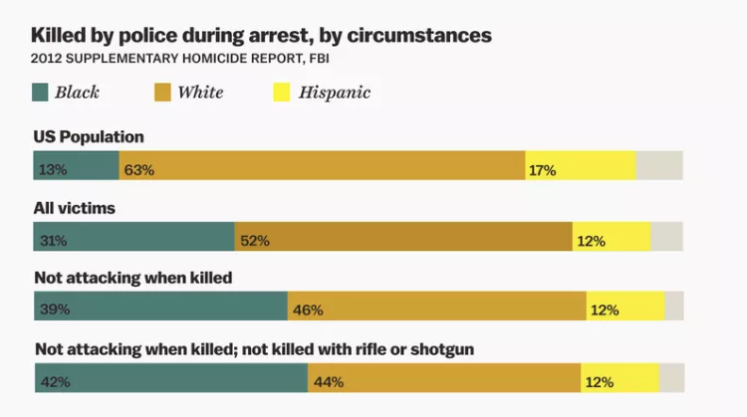

Perhaps a grave issue, then, still exists. Perhaps this research does not contradict disturbing trends found in policing previously, like unarmed Americans killed by the police being twice as likely to be black than white, across the entire nation, in the first half of 2015, or blacks who were not attacking an officer when killed making up 39% of total deaths in 2012, way out of proportion to a small black population, 13% of Americans (compared to 46% of total deaths being white, who are nearly 70% of the American population).

via Vox

As Lind put it,

when people talk about racial disparities in police use of force, they’re usually not asking, Is a black American stopped by police treated the same as a white American in the same circumstances?… They’re saying that black Americans are more likely to get stopped by police, which makes them more likely to get killed.

Putting aside the fact that people are indeed asking that first question, you get the point. As Fryer writes in the study,

The empirical thought experiment here is that a police officer arrives at a scene and decides whether or not to use lethal force. Our estimates suggest that this decision is not correlated with the race of the suspect. This does not, however, rule out the possibility that there are important racial differences in whether or not these police-civilian interactions occur at all.

Glenn C. Loury, a mentor and colleague of Fryer, made this point as well (Making Sense, Harris) when he noted that because the study only looked at arrest data (if there is no arrest or violent incident, there is no police report), it “assumed that the processes leading to an arrest work in the same way regardless of race of the suspect.” The study showed that among the black arrestees there were more women and more unarmed persons, for instance, compared to white arrestees. Loury notes that the police may be “discriminatory in how they decide about arresting people and are quicker to arrest blacks who are less threatening than whites,” and this could possibly explain why the rate of blacks being shot is lower in the study. If the police are arresting blacks who are less of an actual danger, there may be less need to fire a weapon at them. This fact, if indeed a fact, could even coexist with the more abusive behavior against blacks. Discriminatory initiation of interactions and arrests, discriminatorily roughing someone up, but not actually needing to pull the trigger. It’s not contradictory.

Third, this study has not yet been peer-reviewed — where fellow scholars analyze Fryer’s methods to determine validity — nor published in an academic journal. It is currently a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research. Now, this does not at all mean it is seriously flawed, but it may be prudent to wait until the academic process is complete before celebrating the end of racism. Studies that have undergone peer scrutiny are usually the most reliable.

Fourth, Fryer’s data was provided by police departments, whose reports are not always truthful. The Guardian, which the FBI director called a leader in the documentation of police shootings, wrote that Fryer collected his information

largely by coding police narratives rather than considering the testimonials of witnesses or suspects (assuming that the suspects were not killed by the police in the shooting). The study therefore assumes police reports are unbiased sources of information about facts like whether or not the officer shoots the suspect before being attacked.

For this and other reasons, the Guardian sees the study as “misleading.”

Fryer admits that “the penalties for wrongfully discharging a lethal weapon in any given situation can be life altering, thus, the incentive to misrepresent contextual factors on police reports may be large” and that “we don’t typically have the suspect’s side of the story and often there are no witnesses.”

Fifth, and finally, it would be very remarkable if blacks were discriminated against in every arena of policing except for police shootings. Again, Fryer’s look at incidents where shots weren’t fired found significant differences in how blacks and whites are treated in comparable situations:

via The New York Times

It would also be miraculous if experiments conducted with civilians and police officers where both were quicker to shoot armed and unarmed blacks than armed or unarmed whites did not translate into similar problems in the real world.

Studies show police officers associate blacks — innocent blacks included — with aggression and criminality (a stereotype most civilians have as well, whether or not they are aware of it). Studies like one in 2002 show that ordinary civilians in simulations are far quicker to shoot armed blacks than armed whites, and decide quicker to spare an unarmed white than an unarmed black. 2005 research in Psychological Science showed police officers were more likely to mistakenly shoot unarmed blacks than unarmed whites. Happily, the bias diminished with extensive time in the simulation.

The 2006 study mentioned earlier, published in Basic and Applied Psychology, found that during simulations, as Fair and Impartial Policing put it,

Officers with negative attitudes toward Black suspects and negative beliefs regarding the criminality of Black people tended to shoot unarmed Black suspects more often in the simulation than officers with more positive attitudes and beliefs toward Blacks.

Studies from 2007 and 2009 suggest that officers with anti-black biases won’t act on them if they’ve gone through high-quality use-of-force training that diminishes implicit prejudice, a factor related to our first point above — some police departments have much more effective training than others, which can be the difference between life and death for civilians.

Jordan Weissmann writes:

Why would police officers be more likely to get rough with black and Hispanic subjects, but not more likely to fire on them? Fryer suggests it might be a matter of stakes. In theory, police stand to lose a lot more if they shoot the wrong guy than if they give him a blow with a nightstick. But there isn’t hard proof for that narrative, and frankly, given how rarely police appear to be punished after shootings, it’s not especially satisfying.

The Guardian wrote:

Fryer assumed shootings are not necessarily linked to a more general use of police force. Such an assumption seems hard to support: a black person in New York who is stopped by the police is 24% more likely to have a gun pointed at them than a white person, so why would they be no less likely to be shot by an officer? The two seem inextricably linked.

All this is not to say with certainty that Fryer’s work is flawed. But there are reasons to ask serious questions.

Inarguably, it is hardly time for black and white liberals to breathe a sigh of relief and make the Black Lives Matter movement a thing of the past, nor is it time for conservative Americans to pat themselves on the back for being right about racism being fictional. One study — or even two or three — isn’t quite enough for that, especially one that hasn’t been published and may not even contradict other research.

There is a mountain of evidence that both overt and subconscious racism greatly affect the lives of people of color (see The Evidence of Widespread American Racism). Even if, somehow, American police officers were never affected by implicit or explicit biases when reacting or deciding, there would still be much work to be done in the battle against discrimination.

Likewise, even if the police killed civilians without racial bias, mass protests against unnecessary police force would be a very positive thing for our society.

For more from the author, subscribe and follow or read his books.